Overview

The purpose of your balance sheet is to provide a snapshot of what the company owns (assets) and how it paid for what it owns (liabilities and equity) at a given time. Like with the P&L, you map your balance sheet to general ledger accounts from your accounting system to automatically update with actuals.Basics

Balance sheet categories

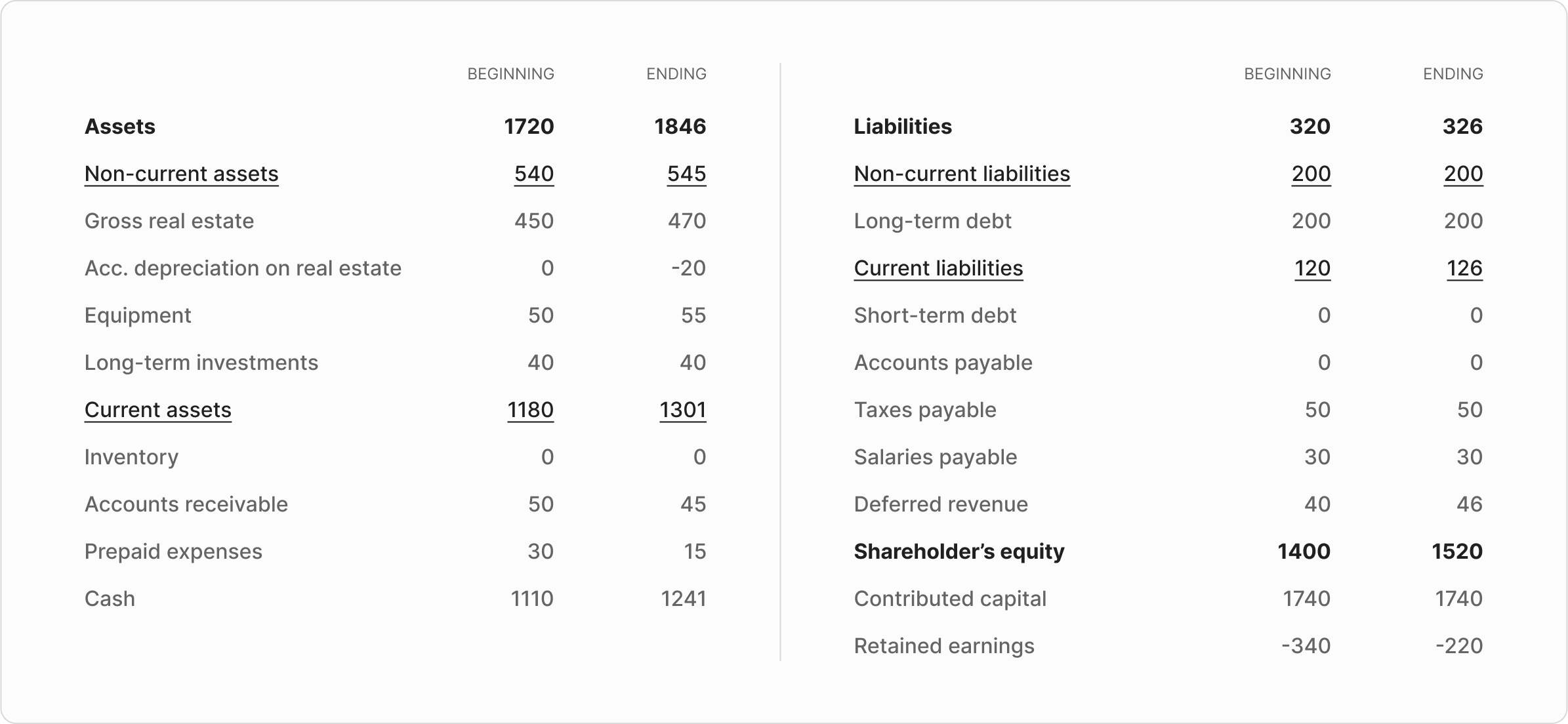

Your balance sheet comprises assets, liabilities, and shareholder’s equity. Assets must always be equal to liabilities and equity.

Accumulated values

Francis shows balance sheet values imported from your accounting system as accumulated values. This is an important distinction between the balance sheet and P&L/cash flow: the balance sheet is a snapshot of your company’s accumulated assets and obligations at a given point in time, while your other statements describe performance over a period of time. For this reason, balance sheet items in charts and reports are typically summarized by ENDING values or DELTA values instead of SUM values.Forecasting the balance sheet

Because the convention in Francis is to present balance sheet values as accumulated values, forecasts must also be accumulated. This is implemented by adding the last period’s value to the forecast formula. Forecasting balance sheet items is a prerequisite for creating a cash flow statement since the cash flow statement is derived from P&L and balance sheet movements. If you’re only interested in cash movements due to P&L movements, you can simplify your balance sheet by creating formulas that assume that the values stay constant. This is the simplest version of a balance sheet forecast. On the other hand, if you want to include cash flow impact from balance sheet movements such as inventory purchases, VAT, tax, and receivables, you need to consider how they change over time.Another way of doing cash flow is the direct method, which lists all direct inflows and outflows of cash (e.g., an inventory purchase in a given period).Francis recommends the indirect cash flow forecasting method derived from the P&L and balance sheet movements. The reason is that the financial model in Francis is mapped to the general ledger of your accounting system, which follows the indirect method. If you set it up the same way in Francis, you create a bridge between forecasts and actuals, allowing you to automatically compare budget vs. actuals and create new forecasts.